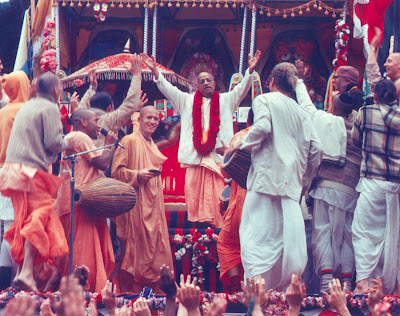

|

| Image courtesy this site. |

Beginning in the 16th century, printed folk music became popular. These were songs printed on sheets of variable lengths, with no music, but under the title would often be a well-known tune the words were to be sung to. These ballad broadsides were popular in Great Britain, France, Germany, Holland, Spain, Italy, and later the U.S.

The earliest musical broadsides cropped up in the 1500s. In 1520, an Oxford bookseller is recorded as selling more than 190 ballads, which is surprising considering the low literacy rate. But broadsides and chapbooks (see yesterday's post) are considered responsible for spurring an interest in reading among the hoi polloi, and the market for cheap reading material catered to this new class of readers. Many of these broadsides were illustrated with a woodcut.

In 1556, England required the legal registration of printed ballads at four pence apiece. The next year printers were required to be licensed by the Stationers' Company in London, the center of ballad and chapbook production. This continued until 1709, and the Company's records reveal over 3,000 entries in that one hundred and fifty year period alone.

Eighty percent of English folk songs that were collected in the early 20th century have been traced to broadsides. These were mostly written in pubs and sold by peddlers, and then eventually in stalls, leading them to also be sometimes called stall ballads. Their heyday was in the 16th and 17th centuries. The "business" was often piratical, and some of these broadsides were printed or glued together so one could get more than one song on a long paper.

But at some point in time, enterprising entrepreneurs came up with a marketing ploy to sell more of the ballad broadsides by having chaunters sing them, using any traditional tune that would fit. These chaunters, or ballad singers, would sing and sell these songs on street corners, markets, fairgrounds, and even executions - anywhere a crown could be found.

Chaunters took the place once held by minstrels. By the end of Queen Elizabeth I's reign, minstrels were put in a class with rogues, beggars, and vagabonds. Grouped with other street orators, such as montebanks or patterers, chaunters often showed little propriety in their speeches and sometimes their songs, so eager they were to sell them. "Patter" became a slang term for speaking. Some chaunters worked with patterers, playing the fiddle while the patterer gave a sales spiel.

When music halls became popular circa 1850, it vitually ended work for chaunters, coinciding with newspapers taking over the service that proclamation and news broadcasts once provided. So chaunters had to adapt. Since the songs from broadsides were often part of the program, chaunters started hawking music hall hits. Music halls offered cheap concerts, and in the mid-1800s introduced the outrageous practice of admitting both genders. Eventually the demand for broadsides faded. In 1800 there were about seventy-five ballad presses operating, but by 1871 there were only four.

Chaunters started performing in pubs and taverns, first selling songs table-to-table, then performing for the whole audience. Those who were successful became the first music hall singers.

Broadside ballads were the literature of the working class, and today provide us with a glimpse of what their lives were like. These ballads moved back and forth from being printed and learned orally, eventually becoming traditional songs. Produced with the working class in mind, they were bought by all classes. Samuel Pepys collected them, ending up with one of the finest collections consisting of over 1,800 ballad broadsheets.

The U.S. also produced them, and some songs went back and forth across the Atlantic. The broadside below is from Northampton, Massachusetts, printed on March 28, 1798. It is a song about "bloomerism", a new fashion for women consisting of baggy pants caught in a cuff at the ankles, allowing a woman the comfort of pants but still obscuring her figure. These caught on in the mid-1800s, and were named for Amelia Bloomer who popularized them.

|

| Image courtesy Kent University library, special collections. |

Printing and reading are thus intertwined with folk music. As new songs were written for old music the words became more notable than the tune. The extant examples of these broadsheets show us the language and culture of a class of people who left no other written record themselves of their existence. This is an entertaining way to learn history.

***************

Unless otherwise noted, all images courtesy of this site.

******************************