|

| Modern-day children reading Dr. Seuss. Image courtesy of scbailey/Wikipedia. |

A picture book combines a narrative with pictures. In the late Victorian era, a number of illustrators became famous for their work in children's picture books. "Toy books", introduced in the latter half of the 19th century, were small paperbacks with a larger number of pictures than text. There illustrations not only helped interpret the stories, but elaborated on them, and were mostly done in color. Three of the best illustrators of toy books are considered the great triumvirate of the time: Randolph Caldecott, Walter Crane, and Kate Greenaway. All three of them worked with color printer and wood engraver Edmund Evans to produce high quality books, and all of them knew each other.

|

| Randolph Caldecott. |

|

| All four illustrations above from the Panjandrum Picture Book. Courtesy of www.gutenberg.org. |

With this encouragement, he quit banking and moved to London in 1872 at the age of 26. A couple of years later he was a successful illustrator working on commission. He lived in the heart of Bloomsbury for seven years, and began to exhibit his work. In 1877 Edmund Evans needed an illustrator and Caldecott was retained to replace Walter Crane. His initial two projects were The House That Jack Built and The Diverting History of John Gilpin, both published in 1878. They were so successful that he did two more each year until his death. He was allowed to choose his own stories to illustrate, and sometimes even wrote his own.

|

| The Babes in the Woods, published 1879. |

|

| "And the Dish Ran Away with the Spoon" from Hey Diddle Diddle and Bye, Baby Bunting, 1882. |

|

| From "The House that Jack Built" in The Complete Collection of Pictures and Songs, published in 1887. |

In 1884 the sales of his Nursery Rhymes (12 books) reached 867,000 copies and he found himself internationally famous. He loved to travel and continued to do so, even after he married (he never had children). He had suffered from poor health since he was a child, and on a tour of the U.S. in 1886, he died in St. Augustine, Florida at the age of 39. He was buried there, but also has a memorial in the crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral in London, and one in Chester Cathedral in his hometown.

The Caldecott Medal was named in his honor. It is awarded annually by the Association for Library Service to Children, a division of the American Library Association. This award is for the artist of the most distinguished American children's picture book. Both it and the Newbery Medal (the first children's literary award in the world, which is given to the most distinguished contribution to American children's literature) are the most prestigious awards for children's books in the U.S.

|

| Walter Crane by photographer Frederick Hollyer, 1886. Platinum print, image courtesy the Victoria & Albert Museum. |

Walter Crane (1845-1915) is often called "the father of children's pictures books". He was a most prolific and influential book creator, and began some of the more colorful child-in-the-garden motifs that became emblematic in many nursery rhyme illustrations. His illustrations for classical tales and fables are "fabulous".

|

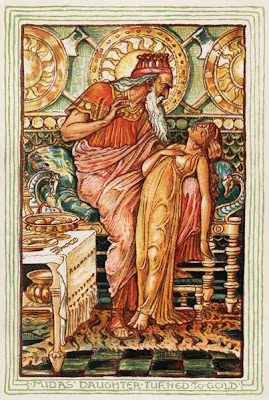

| King Midas with his daughter from A Wonder Book for Boys and Girls by Nathaniel Hawthorne, published 1893. Image courtesy LOC. |

|

| "The Man That Pleased None" from Baby's Own Aesop, 1887. Image courtesy LOC. |

|

| Pegasus. |

He was born in Liverpool to portrait painter and miniaturist Thomas Crane. He was a student of John Ruskin, and a follower of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which he also studied with. During a three-year apprenticeship with wood engraver William James Linton, he was able to study the work that came through by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Sir John Tenniel, and John Everette Millair. Although he admired the art from the late Renaissance, he was greatly influenced by the Elgin Marbles and Japanese color prints.

|

| The Moat and Bishop's Palace, Wells Cathedral is a watercolor that shows his skill with the medium. Image courtesy The Delaware Art Museum. |

|

| One of Crane's wallpaper designs, "Swan and Rush and Iris". |

As part of the Arts & Crafts movement, he became associated with the Socialist movement which believed in bringing art into the daily life of all classes. For this reason he designed textiles, wallpapers, and home decorations. He worked with the Art Workers Guild, and founded the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in 1888. He was vice president of the Healthy and Artistic Dress Union, which began in 1890, whose aim was loose-fitting clothes. He illustrated their pamphlet "How to Dress Without a Corset".

|

| Pamphlet written by William Wheeler. Courtesy peasant-arts.blogspot.com. |

Although Crane was not an anarchist, he contributed to libertarian publishers. In the illustration below he addresses the Haymarket Affair in Chicago, where he made several trips to speak in defense of the eight anarchists accused of murder. At the May 4, 1886 event, someone threw a dynamite bomb at police who were trying to disperse people at a rally in support of striking workers (who wanted an eight-hour workday). The blast and ensuing gunfire killed seven policemen and four bystanders, most of them killed from friendly fire. Four of the eight anarchists arrested were hung and one committed suicide, even though the prosecution conceded that none of the defendants had thrown the bomb.

|

| Crane's portraits of the Haymarket Martyrs, published in the November 1894 issue of Liberty Press. |

From 1865 to 1876 Crane worked with Edmund Evans to collaborate on toy books of nursery rhymes and fairy tales, producing two to three every year. He continued illustrating a variety of books. One of his most famous works was a collaboration with William Morris on the page decoration of The Story of Glittering Plain, published in 1894 by Kelmscott Press. It was done in the style of German and Italian woodcuts of the 16th century. He exhibited his work internationally and lectured and taught.

|

| Kate Greenaway. |

Kate Greenaway (1846-1901) studied at what is now the Royal College of Art in London, which at that time had a separate section for women. Her paintings were reproduced from hand-engraved wood blocks by Edmund Evans. Her first book, which Evans produced, was a collection of simple verses for children. Under the Window (1879) made her reputation as an illustrator. It was made in a costly process where photographs of her dainty watercolors were done on wood blocks, called chromoxylography. Despite advice to the contrary, Evans ran 20,000 copies in a first edition, which sold out immediately.

|

| Illustration from The Pied Piper of Hamelin, 1888. |

|

| The rats of Hamelin. |

She was noted for her depictions of children - all of them dressed in late 18th century and Regency fashions: smocks and skeleton suits for the boys and high-waisted pinafores and dresses with caps and straw bonnets for the girls. The famous department store on Regent Street in London, Liberty of London, used her drawings for their designs for real children's clothing. Mothers in the 1880s and 1890s who conformed with the Arts and Craft movement dressed their daughters in Kate Greenaway pantaloons and bonnets.

|

| The Elf Ring (watercolor). |

|

| A Little Girl in a Muff (watercolor). |

Clothing and accessories were her real forté. She was not as accomplished an artist as Caldecott or Crane, but was adored by the public. She didn't exhibit a real understanding of anatomy. She has been criticized, in fact, for creating doll-like children that lack complexity and spirit. But her fans seemed to prefer her idealized world. She died of breast cancer when she was 55.

|

| May Day. |

The Kate Greenaway Medal was established in England in 1955 in her honor. It is awarded annually by the Charted Institute of Library and Information Professionals to an outstanding work of illustration in children's literature. The first award was given in 1956, and besides 1955 there was no award given in 1958 as well, because no book was considered suitable. The winner receives a gold medal and £5000 worth of books donated to the library of their choice.

All three of these illustrators greatly changed children's literature. They were fortunate to live in a time and place where they had opportunities to meet other artists. The fact that they all knew each other is intriguing. To be a fly on the wall at one of their rendezvous....

***************

Unless otherwise noted, all images courtesy of Wikipedia.

*******************************

No comments:

Post a Comment

NOTE: COMMENTS WITH LINKS WILL NOT BE POSTED!