John James Audubon (1785-1851) Oil on canvas by John Syme, 1826 Currently hanging in the White House. |

John James Audubon, a Haitian-born man raised in France, had a vision. One that resulted in a monumental and important work – Birds of America.

Carolina Pigeon (now called Mourning Dove) |

He had loved birds and nature as a child, and was encouraged by his father to explore and draw what he saw. He was reported to be quite charming, played the flute and violin, learned to ride and to fence, but loved roaming the woods best.

White Gerfalcons |

Although his father had planned for his son to be a seaman, the young Audubon was not fond of navigation or the math required, and failed his officer’s qualification test. He also got seasick easily. His father managed to secure a fake passport and sent him to America in 1803, in order to avoid being drafted in the Napoleonic wars.

Virginian Partridge (Northern Bobwhite) under attack by a young red-shouldered hawk. |

Audubon did well in various family businesses, but really relished his time outdoors, hunting, fishing and drawing. He had a great respect for Native Americans, and spent time with local tribes learning their ways of hunting and their views on nature. He married his neighbor’s daughter, Lucy Bakewell, with whom he shared common interests. They lived in Kentucky and spent time together exploring the local countryside.

Roseate Spoonbill |

In 1812, after Congress declared war with Great Britain, Audubon went to Philadelphia and became an American citizen. Upon returning to Kentucky, he found that his entire collection - over two hundred drawings - had been destroyed by rats. Despondent and downhearted, he decided to redo his work, but this time even better.

Paridae: (clockwise from top right, in pairs) Psaltriparus minimus, Parus atricapillus, Parus rufescens |

His methods for drawing birds were based on his extensive observations from the field. He first killed the birds with fine shot, then wired them into natural poses. He painted the birds in their natural settings, often as though in the midst of motion.

The Greater Flamingo |

Working primarily with layers of watercolor and sometimes gouache, he added pastels or colored chalk for softness. Audubon drew all the birds life-size and placed smaller birds in settings with branches, flowers, fruit and berries. He grouped several species in some drawings on the same page to show contrast. His poses were contrived to reveal as much of bird anatomy as possible, achieving both scientific and artistic efficacy.

He took his new collection of drawings to England in 1826. American printers had not been very responsive to his enthusiastic plans to publish life-size prints of hundreds of bird species made from engraved copper plates and hand-colored.

Birds of America consists of 435 prints printed on sheets measuring 39 by 26 inches. The printing costs were $115,640 (over $2,000,000 by today’s rates). Besides arranging for the production of his grand opus, he tirelessly promoted it. He raised the money from advance subscriptions, oil painting commissions, exhibitions, and even the sale of animal skins from his hunts.

Over fifty colorists were hired to apply each color in an assembly line. The original edition was engraved in aquatint. Robert Havell took over the project when the first ten plates of engraver W. H. Lizars were found subpar. By the 1830s, lithography replaced the aquatint process. He called the new size the double elephant folio since it was double elephant paper size.

Criticized for not ordering the plates in Linnaean order (like a scientific treatise), he was more interested in providing a visual tour for the reader. King George IV was a subscriber along with others of nobility. He gave a demonstration of how he propped the birds with wire to arrange their poses. A student at the time, Charles Darwin, was at that demonstration. Darwin quotes Audubon three times in The Origin of Species and in later works.

Golden Eagle |

Audubon has had a vast influence on natural history and ornithology. His high standards set the bar for future works. Among his accomplishments were the discovery of twenty-five new species and twelve subspecies. In his journals, he warned about loss of habitats and over-hunting. Birds that have become extinct, including the Carolina Parakeet, Passenger Pigeon, and Great Auk, are only known to us from his prints. This follows in the steps of a predecessor, Ustad Mansur, the Mughal artist who most famously left us with a true depiction of a dodo bird.

His next work was a sequel entitled Ornithological Biographies, written with a Scottish ornithologist, William MacGillivray. Both books were published between 1827 and 1839, but separately to avoid having to provide a copy of Birds of America to the Crown libraries, as required by law for any books with text.

Ruffled Grouse |

In 1839-1844, he published an octavo edition of Birds of America with an additional 65 plates. These were approximate 10-1/2 by 6-3/4 inches. The earliest editions were bound in seven volumes, editions after 1865 in eight volumes. This edition was first published in fascicles (parts) in an effort to make it more affordable, and therefore accessible to libraries and to more people. Each fascicle cost $1, and the entire set cost $100. Once collected, most subscribers had them bound in volumes.

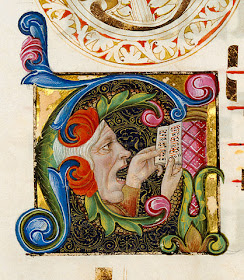

Fascicle of Part 4 |

The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, his final work which focused on documenting mammals, was written in collaboration with Rev. John Bachman, who supplied most of the scientific text. This was completed by his sons and son-in-law posthumously.

Snowy Owl |

John Woodhouse Audubon devoted himself entirely to continuing the work of his father. They worked together on the series The Quadrapeds of North America (the “Viviparous” was dropped), but when John James became too ill to continue, John Woodhouse ended up doing most of the drawings. Because of the dangers of working closely with live animals, caged or dead ones were used as models. Since this was more unwieldy than staging bird poses, their animal paintings were not as successful, and are rather gloomy.

Mountain Brook Minks, 1848 by John Woodhouse Audubon. Image courtesy of National Museum of Wildlife Art |

Despite being under the shadow of his father, John Woodhouse’s contributions are valuable. His brother, Victor Gifford Audubon, also continued the family tradition of wildlife painting, but is the least known of the Audubon family.

Passenger Pigeons (now extinct) |

Lucy Audubon sold all 435 of the original watercolors to the New York Historical Society, after her husband’s death. Desperate for money, she later sold all but 80 of the original copper plates to the Phelps Dodge Corporation, who melted them down and sold them for scrap.

Sotheby's Mary Engleheart shown with copy of Birds of America auctioned December, 2010. Photo by Pitarakis/AP. |

Considered the world’s most expensive printed book, one of the 119 copies still extant was sold on January 20th of this year at Christie's. This was the "Duke of Portland" set acquired by William Henry Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, the fourth Duke of Portland (1768-1854) some time after 1838. Reported to be in excellent condition, it was sold to a private American collector for $7,922,500. The highest amount paid for the four-volume set was in December of 2010 when Michael Tollemache, a London fine art dealer and bird lover, purchased one for $11.5 million. Of the 119 remaining copies of the book, only a few are in private hands, the rest (estimated to be 108) belong to libraries, universities, and museums.

John James Audubon was a talented artist and salesman, whose exacting efforts to record the creatures he loved yielded one of the most impressive books ever made. A unique man, he envisioned his dreams and brought them to fruition. That is certainly worth millions of dollars.

***************

Unless otherwise noted, images courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

An earlier version of this post appeared on Booktryst.

******************************